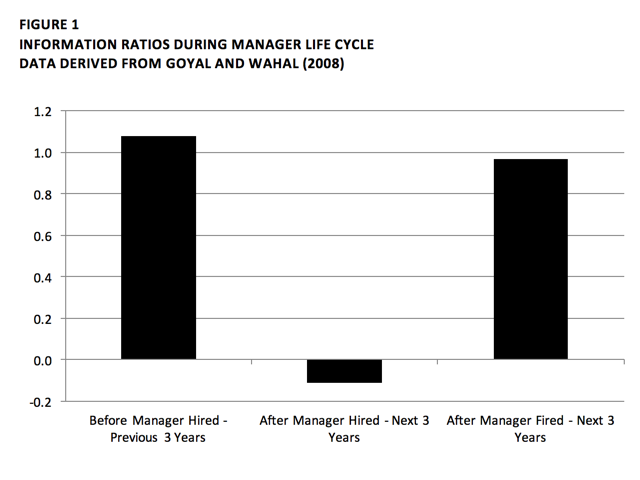

Choosing active managers is difficult, time consuming and often frustrating, not only because the process is grueling but also because, once hired, those active managers often disappoint. Indeed, the most common complaint we hear from asset owners is their active managers do not perform as expected. While anecdotal evidence of this phenomenon seems to be everywhere, a paper by Goyal and Wahal (2008) analyzes 1800 plan sponsors over a 10 period and produces the same finding.

Figure 1 is derived from data in this paper and suggests manager selection follows a particularly nasty cycle. Managers seem to be hired at the peak of their performance (did anyone ever hire a manager that was underperforming?) only to subsequently underperform their rosy track records – and this is where the complaints start. Eventually asset owners get fed up with poor returns and fire these managers only, of course, to see these same managers then outperform once again. Although we can’t quantify it accurately, the amount of wealth destruction stemming from this cycle must be enormous.

Is it even possible for managers to deliver persistent excess returns, free from the cyclicality found by Goyal and Wahal? This was the fundamental question first addressed by Carhart (1997) who analyzed nearly 2,000 mutual funds over a 30 year period. He found that fund managers generate excess returns from two sources: first, from exposure to common style factors like value, size and momentum and; second, from the skill or ‘stock picking’ ability of managers. Table 1 decomposes the returns of managers with positive excess returns and groups them into deciles. In all but the first decile the supposed skill or ‘stock picking’ ability of the manager actually reduced returns while common style factor exposure was the sole source of positive performance. In the first decile skill contributed a mere 2 bps while factors added 60 bps.

TABLE 1

DECOMPOSITION OF MANAGER EXCESS RETURNS (MONTHLY)

DATA DERIVED FROM CARHART (1997)

|

Excess Return Decile |

Common Style Factor Exposures |

Skill “Stock Picking” |

Monthly Excess Return |

||

|

1(High) |

0.60% |

+ |

0.02% |

= |

0.62% |

|

2 |

0.53% |

+ |

-0.06% |

= |

0.47% |

|

3 |

0.52% |

+ |

-0.03% |

= |

0.49% |

|

4 |

0.48% |

+ |

-0.05% |

= |

0.43% |

|

5 |

0.52% |

+ |

-0.13% |

= |

0.39% |

|

6 |

0.51% |

+ |

-0.11% |

= |

0.40% |

|

7 |

0.55% |

+ |

-0.17% |

= |

0.38% |

|

8 |

0.56% |

+ |

-0.16% |

= |

0.40% |

|

9 |

0.56% |

+ |

-0.19% |

= |

0.37% |

|

10 (Low) |

0.62% |

+ |

-0.43% |

= |

0.19% |

While some managers do, of course, get lucky in picking certain stocks, Carhart argues their skill is highly mean reverting, suggesting managers that do well today may not do well tomorrow. The lack of persistence in skill is, no doubt, a primary cause of manager cyclicality and the Goyal and Wahal phenomenon. In contrast, Carhart finds:

“Common factors in stock returns…almost completely explain persistence in equity mutual funds’ mean and risk-adjusted returns”

…in other words, a potential way out of the vicious cycle. A more recent study by Grinblatt et. al. (2016) updates the Carhart study and re-confirms many of the original findings.

The message here is simple: instead of wasting your time in the losing game of manager selection, focus more of your attention where returns are really generated, i.e., common style factors. Below are a few of the creative ways investors have employed factors like size, volatility, dividend yield and quality in their portfolios.

- A U.S. pension fund has employed low-volatility strategies in their global large-cap core portfolio, freeing up risk to be better utilized in small-caps and emerging markets. The aggregate equity portfolio was optimized to yield an aggregate beta of 1.0 but with less absolute volatility than their benchmark.

- One large US insurance company recognized dividend yield as an excellent hedge against inflation given the correlation of dividend yield on large-cap US stocks and inflation exceeded 0.75 the last three decades. A movement toward high dividend yielding stocks that were also of high quality allowed this company to help insulate their liabilities from inflation, but without the low total returns associated with TIPS and floating rate bonds.

- Another large US insurance company is re-optimizing its risk-based capital (RBC) in response to a change in RBC requirements promulgated by the NAIC (National Association of Insurance Commissioners). To take advantage of the lower RBC charges associated with lower beta equity portfolios, they are shifting exposure to low-volatility public equities to free up capital for private equity and commercial real estate.

Manager selection is arduous and often counter-productive. Asset owners need to focus less on selecting active managers and more on implementing prudent factor exposures. The greater control offered by factor investing allows these asset owners to design their portfolios around specific outcomes and, of course, the higher returns and greater persistence of factors is nice too.

References

- Carhart, Mark M. "On persistence in mutual fund performance." The Journal of finance 52.1 (1997): 57-82.

- Goyal, Amit, and Sunil Wahal. "The selection and termination of investment management firms by plan sponsors." The Journal of Finance 63.4 (2008): 1805-1847.

Grinblatt, Mark and Jostova, Gergana and Petrasek, Lubomir and Philipov, Alexander, Style and Skill: Hedge Funds, Mutual Funds, and Momentum (January 6, 2016). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2712050or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2712050