Factor-based investing appearsto be the only option in this period of slower markets and higher rates

While there is nothing we can do about low beta returns and many have become highly skeptical of traditional active stock picking as a consistent source of return, it seems that in the coming years factors may not only be the best option—but the only option. Over the next five years we expect macroeconomic, market and monetary policy conditions to be aligned with strong factor performance.

Expected returns are disappointing

Our return expectations on major asset classes like equities, bonds and hedge funds have declined over the last several years. In 2012, we expected a traditional 60/30/10 portfolio to generate a return of about 6.2%. In 2016 that figure dropped to less than 4.5%, well short of the return targets used by most pensions, foundations and trusts. Importantly, our equity forecast has dipped below 6% for the first time in recent history.

Our research tells a different story for factors

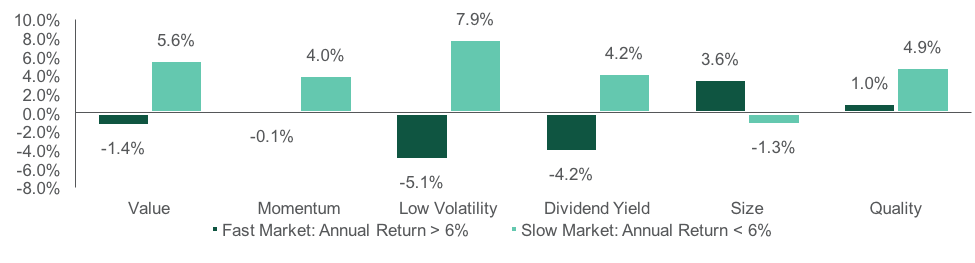

While the falling expectations are cause for concern, there is no need to panic. As Exhibit 1 shows, factor performance is at its best when market returns are lackluster. Specifically, factor returns in heady markets tend to fall behind. In contrast, factors tend to outperform significantly when market returns are coasting. In these middling conditions, exactly where we expect to be over the next five years, factor exposures like quality, value and low volatility can add materially to equity performance, thereby narrowing the gap between realized and target returns.

Slower markets can translate into factor outperformance

Admittedly, this differential in factor returns is somewhat counterintuitive. It seems the word on the street is that factors, especially value and momentum, are in peak form when markets are a go-go. However, mechanically speaking this cannot be the case. Very strong markets require the preponderance of stocks to be moving in the same direction: up. In other words, individual stock returns are necessarily highly correlated or, putting it another way, the dispersion of returns tends to be quite low. In this scenario factors really can’t outperform because nothing is underperforming and, hence, there is nothing to beat.

The story changes when markets slow. Dispersion among stock returns tends to increase, which gives factors the opportunity, although not necessarily the means, to beat benchmarks. While pairwise correlations among stocks were elevated in the period from 2012 to 2015, a time of strong markets and disappointing factor returns, correlations have come down in 2016 and remain low today. This set the stage for resurgence in factors which began in earnest, not surprisingly, in early 2016.

Exhibit 1: factor excess-return performance in slow and fast markets: Factor excess returns versus the Russell 3000 Index have historically from 1979 to 2016 been stronger for slower markets (annual equity returns less than 6%) than for faster markets (annual equity returns more than 6%). We expect slower markets in the next five years.

Source: Northern Trust Asset Management, Russell 3000 Index

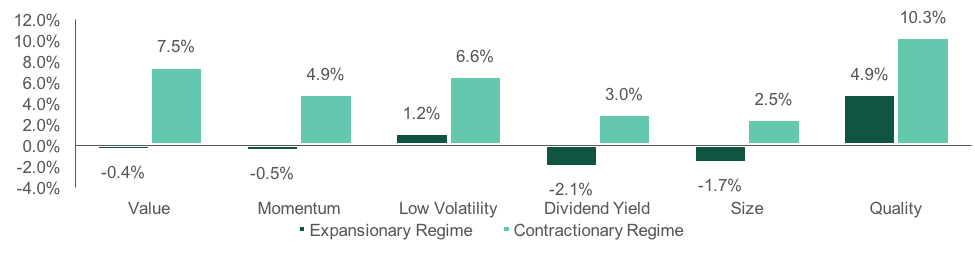

Naturally, if dispersion drives factor performance we must ask why dispersion fluctuates. Dispersion and factor returns may be related to prevailing monetary conditions. We see a strong relationship between the policy stance of the Federal Reserve and performance, with factors doing better during periods of contraction. Exhibit 2 demonstrates this historical pattern.

Within a contractionary monetary regime the central bank is effectively engineering a recession, the impacts of which will vary considerably by sector, industry and individual company, thus generating a broad and varying dispersion. In contrast, when policy is expansionary the effects tend to be more homogenous. For example, companies simultaneously benefiting from “easy money” cause dispersion to narrow. In short, contractionary monetary policy leads to more dispersion which leads to higher factor returns. Recent signaling from the Federal Reserve is unambiguously contractionary.

Factors entering their prime

While the outlook for passive benchmarking is sour and the efficacy of traditional active management is suspect, we must not be deterred in our effort to achieve equity performance targets. Factors are entering their prime as the various stars are aligning: low market return expectations, unambiguous contractionary central bank rhetoric, and a forecast for several interest rate increases over the coming year, all portending strong factor returns. For many investors the only hope of meeting equity performance goals may well rest with factors. The time is now.

Exhibit 2: excess factor returns during expansionary and contractionary federal reserve policies: Excess returns of factors versus the Russell 3000 Index have performed better during contractionary policy, the Fed’s stance now.

Source: Regimes defined by Bae, Kim and Kim (2011) and Romer and Romer (2004), extended by Northern Trust Asset Management quantitative research. Historical data from 1979 to 2016.

References

Bae, Jinho, Chang-Jin Kim, and Dong Heon Kim. "The evolution of the monetary policy regimes in the US." Empirical Economics (2012): 1-33.

Carhart, Mark M. "On persistence in mutual fund performance." The Journal of finance 52.1 (1997): 57-82.

Ehrmann, Michael, and Marcel Fratzscher. "Taking stock: Monetary policy transmission to equity markets." (2004).

Grinblatt, Mark, et al. "Style and Skill: Hedge Funds, Mutual Funds, and Momentum." Mutual Funds, and Momentum (January 6, 2016) (2016).

Kalay, Alon, Suresh Nallareddy, and Gil Sadka. Conditional Earnings Dispersion, the Macroeconomy and Aggregate Stock Returns. Working paper, Columbia University, 2014.

Romer, Christina D., and David H. Romer. "Choosing the Federal Reserve chair: lessons from history." The Journal of Economic Perspectives 18.1 (2004): 129-162.