The price of quality has increased lately, but not to extreme levels; investor benefits should remain

Some say that high quality companies are overly expensive and question whether they should be currently held in a portfolio. While the price of quality certainly has risen, valuations are not extreme and investors should place special consideration on the benefits they may receive from investing in high quality companies.

From German automobiles to Italian leather goods, we are used to paying a premium for high quality products. Whether it’s cutting-edge engineering and market-leading reliability, or superior flair and workmanship, for certain products we recognize the benefits that often come with an increased price tag. But this phenomenon is not limited to cars and handbags.

The question is often asked about whether investors should pay a premium for purchasing high quality stocks. There have been a number of articles in recent times that have taken the view that the high quality companies are overly expensive in the market and trade at a significant premium, leading to the question about whether they should be held within a portfolio.

The Quality Price Tag: A Closer Look

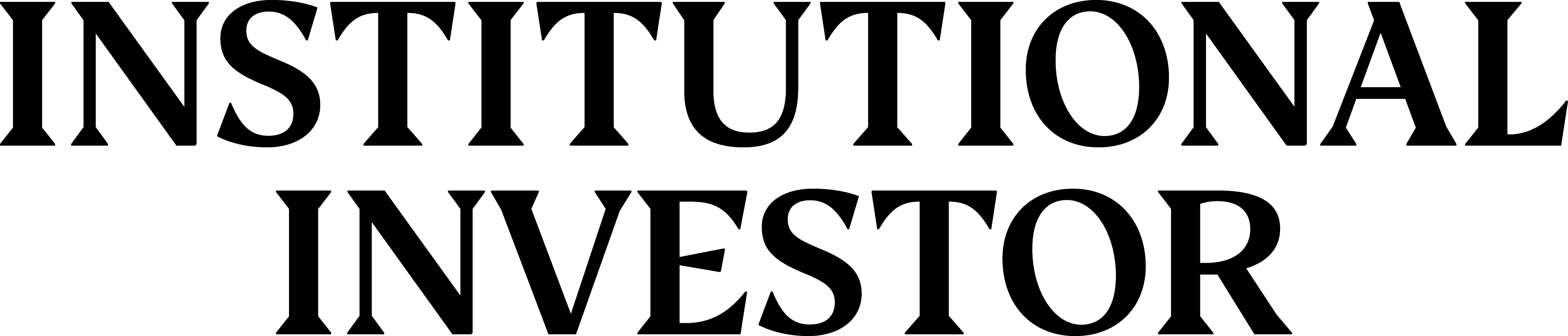

Exhibit 1 shows the valuation of quality as measured by the price/book premium compared to the MSCI World index. Our research shows that although high quality stocks are currently priced at levels above their long run history. At just over one standard deviation from the long run average, we do not see this to be extreme.

The Dimensions of Quality

Our proprietary quality score assesses a company’s ability to:

- convert assets into sales, earnings

- turn equity into returns

- convert investment capital into returns

- self-finance

- remain solvent

- grow prudently without becoming overextended

See our paper A Superior Approach to Quality.

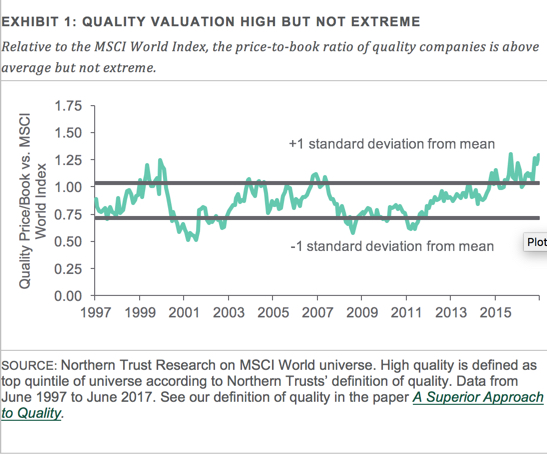

Quality stocks, almost by definition, tend to be lower risk and are more profitable than the market as a whole. As such, it makes sense that the average valuation for quality stocks is at a premium when compared to the broad market. Quality itself is one of a small number of compensated factors and has shown the ability to provide a meaningful improvement in absolute and risk-adjusted returns over time, as seen in Exhibit 2.

No Need for Timing

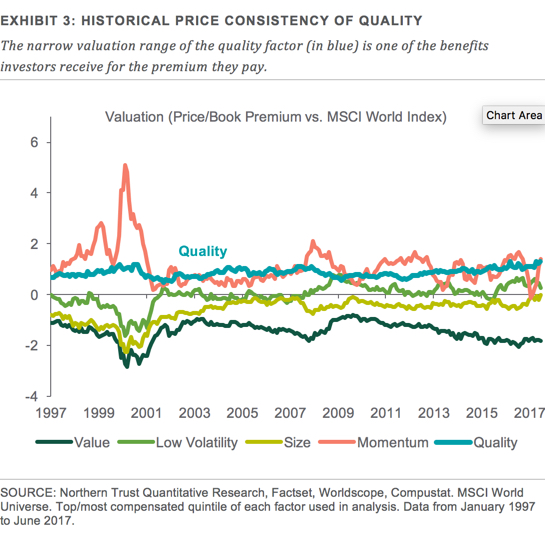

What is perhaps more interesting is that this outperformance of quality can be seen against a backdrop of relatively stable factor valuation through history. We know that all factors are cyclical, and that these cycle lengths differ from factor to factor. However, we also see that the quality factor has a narrower range of valuations over time when compared to other compensated factors. Exhibit 3 charts this variation of valuations over time, again using the price/book premium for each factor. This relative consistency of pricing is in stark contrast to the other factors, with the comparison to momentum being most dramatic.

The narrow valuation range of quality can also provide us with additional comfort that despite being relatively more expensive than the value factor, it can be less painful at times of mean reversion.

The narrow valuation range of quality can also provide us with additional comfort that despite being relatively more expensive than the value factor, it can be less painful at times of mean reversion. We do not see the same extreme snap-backs in the valuation levels of quality that we see in some other factors. This relative consistency of pricing can also help minimize the concern around the question of when to invest in the quality factor, i.e., there is never really a bad time. However, we also note that successfully making calls around factor-timing is hard and not something we recommend without a crystal ball.

To help further mitigate risk of underperformance over time, we frequently see the benefits of combining factors. The combination of quality with the value factor is particularly beneficial. Naturally, the value factor is consistently inexpensive relative to the market, by definition. As such when combined with the quality in a dual-factor or multifactor framework we find that we can continue to buy high quality companies that are also relatively inexpensive. This compelling combination of quality and value is a great way to distinguish between cheap stocks with strong fundamentals and cheap stocks with poor fundamentals. Combining multiple factors within a single strategy brings a portfolio construction challenge that we believe is best addressed in a bottom-up/intersection approach to help minimize exposure to unintended or undesired risk — see our factor intersection paper Combining Risk Factors for Superior Returns.

There’s No Wrong Time

As a systematically compensated factor, quality investing has the potential to provide improved risk-adjusted returns over time, with a robust factor definition key to success. With the relative consistency of quality valuations through time, the impact exposure to the factor at the “wrong time” is greatly reduced and the mean reversion in pricing is not as painful as it can be for other factors. Even if quality stocks may be priced higher than other factors, they can still be good buy – and perhaps like a German automobile — be a more reliable and efficient way to reach your destination.